On 30th September 2015, BBC reported the lynching of a 50-year-old man named Mohammed Aklaq in Dadri, Uttar Pradesh.[i] Aklaq and his son Danish were dragged out of their home on to the streets by a group of men and hit with sticks and stones. While Aklaq succumbed to his injuries, Danish was admitted to a hospital. This violent act was the culmination of the villagers suspecting that the family had slaughtered a cow. Aklaq’s case was the start of the many cases to make it to the headlines for the same reason – ‘mob lynching’.

Two years later, Pew Research Centre ranked India 4th to have the highest social hostilities involving religion.[ii] And in June 2017, IndiaSpend found out that ‘63 attacks fueled by the suspicion of cow slaughter or beef consumption have been reported from across the country since 2010.’ The report further adds, ‘At least 28 persons were killed in these attacks – 24 or 86% of whom were Muslims. Half of the attacks occurred in states run by right-wing governments.’[iii] However, it is important to keep in mind that the actual numbers of lynching remain ambiguous, given the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) doesn’t maintain a separate record for mob lynching.

It is seen that the reason NCRB doesn’t have data on mob lynching is that it is not seen as a specific offence under the Indian Penal Code. Currently, lynching is covered under Section 302 (murder), 307 (attempt to murder), 323 (causing voluntary hurt), 147 (rioting), 148 (rioting armed with deadly weapons) and 149 (unlawful assembly). The real question then would be why does the state not recognise lynching as a crime in itself and not club it with murder or rioting? And what exactly is taking the Indian state so long to come up with special legislation that deals with mob lynching? States like Manipur and Rajasthan have already passed bills to deal with the same. A possible answer might emerge if we look into what exactly goes into the making of a law.

Cambridge dictionary defines legislation as “a law or set of laws suggested by a government and made official by a parliament.” Communication of this information entails engagement with questions of what norms apply and how. In this context, language becomes important.

Language influences our world view and what we learn from society. Wilhelm von Humboldt, a Prussian philosopher and linguist, believed that ‘language is a means not only to describe reality but also discover the reality.’ The language itself gets to be what it is and contains the words it does from the culture it’s found in. And therefore, all societies have ideas that are peculiar to their culture and which either can’t be translated in other languages or, when translated, loses out on their original essence.

It becomes interesting then to note that there is no word equivalent to lynching in most Indian languages except for in Bengali, which is called ‘ganapitaai’ (Malreddy, et al., 2019).[iv]The word lynching originated in the United States in the mid-19th century and was used to describe the extra-judicial murders of African-Americans by groups of white people. Lynch came from the word ‘lynch law’(coined by Charles and William Lynch) which was used for this process of execution without trial. This cultural difference in the language pattern is reflected in how people analyse the world around them. This then would mean that the concept of lynching itself becomes alien to the subcontinent and for the population. It isn’t any different from the murders that are committed.

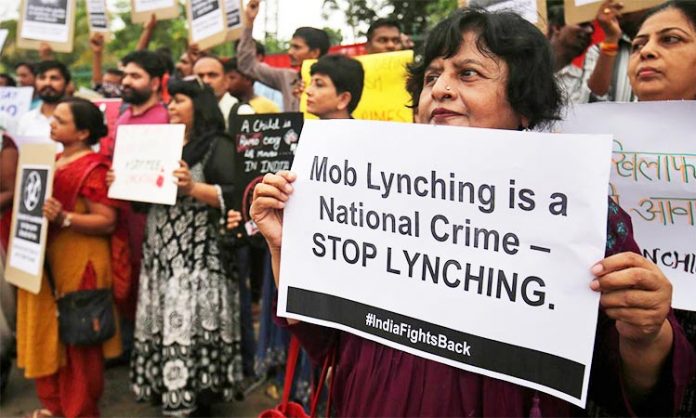

Time and again, this has been exploited by politically influential people who have claimed that lynching is a ‘Western-Ccnstruct’ which therefore, can’t be used in the Indian context. One of the people to say so was the RSS chief, who felt that lynching is not a word from Indian ethos and that it is a plot that’s being used to defame the country.[v] For them, it’s the same as any other law and order situation that can be dealt by with the laws that already exist. However, lynching, unlike murder, is a ‘Public Spectacle’ wherein a group executes a person for an alleged offence. What is even more horrifying is that the data points towards this being committed against religious minorities and people coming from marginalised castes for transgressing social norms. It is an extreme form of social control.

Bernhard Grossfield, in his work Language and the law (1985),[vi] expresses that a law that doesn’t correspond to the linguistic sensitivities of our society is not regarded as “our law” but is seen as something foreign. This does make sense, but the non-existence of certain words or concepts in our culture doesn’t mean we live in denial. Does reality not create language? Isn’t our constitution said to be flexible enough for amendment according to the changing socio-economic context? Don’t states have the legal obligation to protect and promote human rights and provide justice?

There may be no word equivalent to lynching in most Indian languages, but there is one for justice and that the victims deserve.

[i] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-34398433, accessed on 3rd April 2020.

[ii] https://www.thequint.com/news/world/india-has-4th-highest-religious-hostilities-below-syria-and-iraq-pew-research-center, accessed on 3rd April 2020.

[iii] https://thewire.in/government/cow-related-violence, accessed on 3rd April 2020.

[iv] Malreddy, P. V. (Ed.). (2019). Violence in South Asia : Contemporary perspectives (1st ed.). Taylor & Francis Group.

[v] https://scroll.in/latest/939790/lynching-is-a-western-construct-used-to-defame-india-claims-rss-chief-mohan-bhagwat, accessed on 3rd April 2020.

[vi] Language and the law. (1985). Journal of Air Law and Commerce, 50(4), 793–803. https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc/vol50/iss4/10/

***

KS. Vaishnavi is a 2nd-year student studying Sociology & Political Science in the Department of BA Programme, Miranda House, Delhi.