Link to part one can be found here.

The Coca-Cola company has and continues to be a significant fixture in global corporate consumerism. Weathering (and sometimes even appropriating) critique from academia, politicians and leaders of countries worldwide, especially from the Global South, environmentalists, and activists, Coca-Cola remains a major brand with global recognition, dominant market share, and a loyal consumer base. Coca-Cola’s advertising strategies over the decades exemplify and strengthen its domination in our collective cultural imagination.

Globalisation brought about a twofold process of “the particularisation of the universal and the universalisation of the particular,” and this tension can be seen in the policies adopted by ad agencies (Mazzarella 2004). For instance, William Mazzarella (2003), in his ethnographic study of a Bombay advertising firm in the late 90s, shows this tension between the two concepts.

The project of Indian consumer citizenship had several challenges. It had to reconcile universal aspirational consumerism and a particular status class based on consumption and a ‘global’ consumption identity and the claim that globalisation would mould to fit Indian tastes, values, and culture. Companies wanted to position themselves as ‘world-class’ but also fundamentally ‘Indian’. A convenient solution at this juncture became the call for a ‘cosmopolitan Indian-ness’. An “a very Bombay” image was the campaign run by the agency under study. Such ‘global cities’ mediate between the two logics of contemporary capitalism: dispersal and centralisation, localisation and globalisation (Sassen 2001). The image of the ‘cityscape’ of Bombay performed this function – it laid an inclusive claim to the multitudes of masses that live in the city while also sanitising and capturing the aspirational image of the same to make an exclusive consumerist claim at the same time (Mazzarella 2003).

In this context, the Coca-Cola company developed one of the earliest models for producing and disseminating transnational branded marketing, in what came to be called “pattern advertisement”. Coca-Cola’s pattern advertising insisted on uniformity, although allowing for slight local variations. This was a precursor to multinational corporations’ ‘glocal’ approaches in later decades (Ciafone 2019). Connotations and thus the representation in ads associated with the brand also differed, keeping in mind the values in different cultures. For instance, advertising in predominantly Muslim countries sold Coca-Cola as the perfect drink after a Ramadan fast. The implicit message is that it is a drink appropriate for a modern and traditional nation. Coca-Cola’s brand thus allowed for a certain degree of fluidity, which would appropriate the necessary values to sell the product and the ‘Coke lifestyle’ to every consumer, global, local, or both.

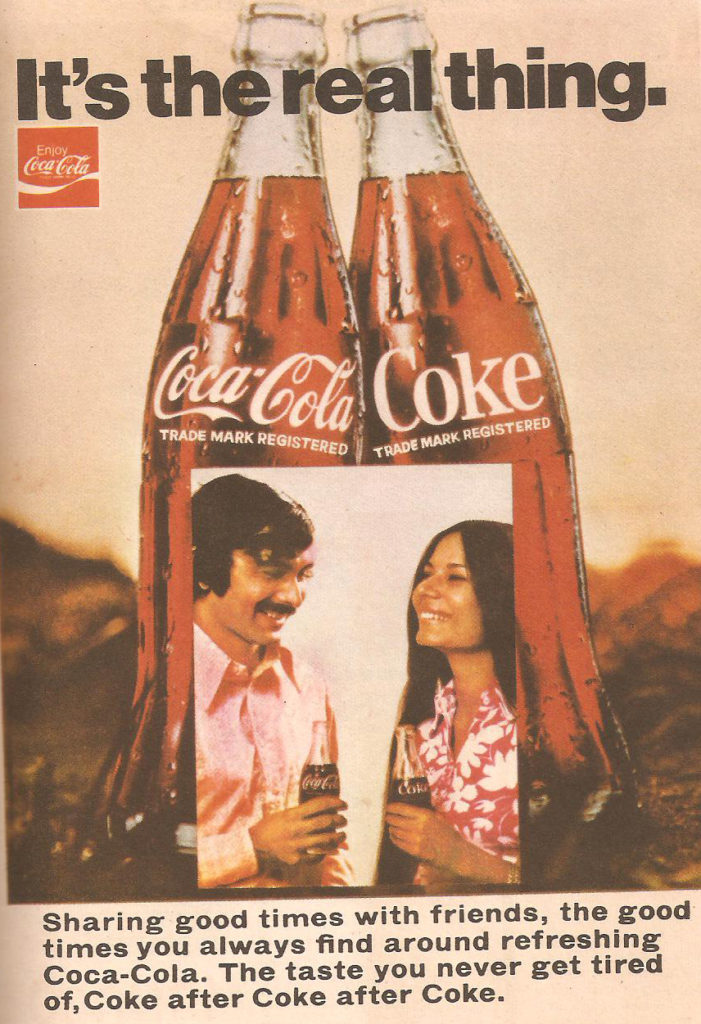

Another characteristic of Coca-Cola ads is their simultaneous inclusive and exclusive branding. Ads would emphasise that “50 million [Cokes were] consumed every day”, making it the “most widely consumed soft drink in the world”, but at the same time, the images in the ads did not strive to be overtly ‘commonplace’. The models hired and the life depicted a very particular high economic and social class – overwhelmingly white, suburban, and well-to-do – the perfect aspirational American dream (Ciafone 2019).

In the early 1960s, the Coca-Cola company linked its brand to several catchy jingles, repeatedly playing in tv and radio spots. These ‘earworms’ wriggled into listeners’ ears from repeated exposure were designed to stick with the listener and sung, whistled, or hummed, sometimes even unknowingly long after the commercial had ended. This can be seen as Appadurai’s conception of Mauss’s body techniques (Appadurai 1996), where it becomes a site for inscribing social disciplines such as consumption, particularly consumption of the Coca-Cola lifestyle. He contends that such consumption is an illusion, and a general theory of consumption has to be located and contextualised in time ‘as history, periodicity, and process’.

Consumption, as a feature of the cultural economy, falls into the mode of repetition and habit. In all its social contexts, consumption is centred around Mauss’ “techniques of the body” (Mauss 1973). As the body is an intimate arena for reproduction practices, it is also an ideal site for inscribing social disciplines (such as consumption). This inertial logic of repetition is further socialised by the ruling classes through larger regimes of periodicity, such as seasonal shopping around festivals, for instance.

One of Coca-Cola’s most enduring catchphrases, “It’s the real thing”, also originated during this period to capture the cultural and political turn of the 1960s youth. “The Real Thing” campaign asserted the genuine, essential and authentic qualities of Coke. However, ‘real’ did not mean actual product attributes, such as taste, size, or packaging, but rather the very notion of authenticity was being advertised. Following Judith Williamson’s analysis, the notorious ‘secret formula’ behind the drink was the feeling it evoked rather than the material formula itself. Freed from referring to anything ‘real’ about the product itself while selling ‘realness’ as the commodity, highly mediated advertisements sold constructed brands as self-referential signs. Brands, their images and connotations, give value to their products and not the other way around (Williamson 1978).

The defining moment in Coca-Cola’s advertising was in 1971, with their iconic ‘Hilltop’ or ‘I’ll Like to Buy the World a Coke’ campaign. The ad opens with youth from ‘all over the world’ – they are racially and ethnically coded to signify ‘diversity’ and its global character’. These youth are standing together on top of a lush, green hill, holding a bottle of Coke in their hands and singing, “I’d like to buy the world a Coke and keep it company”. The victory of this iconic ad lay in the fact that it was not advertising the product Coca-Cola at all – but something bigger than Coca-Cola.

A few years after the “It’s the Real Thing” campaign’s first racially integrated ads, “Hilltop” endeavoured to portray the diversity of the entire world. Graham’s voice and the image of the young, white woman on-screen lead the commercial and the chorus, with the rest of the group slowly building as the camera pans to take in different members, side by side in long, well-ordered, straight lines. They comprise the “First United Chorus of the World,” a tokenist multicultural group of representatives, distinguished by traditional folk costumes, each standing for a people, and together unthreateningly suggesting the possibility of global harmony (Ciafone 2019).

World peace is never directly mentioned in the text but heavily implied. The commercial and its song hit a strong chord with consumers and listeners. In fact, the song in the commercial, “I’d Like to Teach the World to Sing”, sold one million copies that year and became a top 10 hit. Ultimately, the ad sold a perfect, uniformly palatable version of utopia – a utopia only possible under corporate globalism and a bottle of Coke. It projected a neoliberal single world order, where diverse people could easily freely and peacefully share in the consumption of Coca-Cola.

Later years also saw Coca-Cola sticking to this same strategy in its approach to new campaigns. The commercials for “Coke is It” in the 1980s and “Always Coca-Cola” in the 1990s developed universal themes and generic situations that could be applied transnationally with slight local variations. Coca-Cola has also adopted and banked on seasonal advertising, most notably the “Holidays are Here” campaign running since the mid-90s. For many consumers, it has become the sound heralding Christmas. This seasonality is another repetition used to build regimes of periodic consumption (Appadurai 1996).

Finally, Coca-Cola’s most recent 2011 “Share a Coke” campaign encourages people to ‘share a Coke’ with family and friends. The 150 most popular names replaced Coke’s name on the bottle. In the most brazen explicit form of consumers becoming the product itself, Coca-Cola sold consumers to themselves (Williamson 1978). Themes of ‘family’, ‘friends’, and ‘togetherness’ are evoked in a masterstroke of consumption. There is virtually no difference between the product and the consumer. The name of the consumer, and by extension, their identity, becomes the product.

Through this two-part essay, I have attempted to make a conceptual and theoretical study of the relationship between capitalism, consumption and advertisement in the globalising world. Advertising and advertisements are a rich field, and different and competing theoretical frameworks have been used to analyse the same. Rather than seeing advertisements as a hegemonic monolith of global capitalism, more nuanced reading would view them as co-constitutive. They are as much as a product, along with a producer, of cultural and economic systems.

The case of Coca-Cola advertisements is a perfect prism to observe this relationship – not only does Coca-Cola profoundly shape generations of consumers, but it is also a perfect product of the corporate globalist system. Co-opting other narratives into its brand, Coca Cola perfected its image as the ultimate symbol of globalisation. As shown throughout this essay, its appeal often lies in its globalised nature rather than the product itself.

References:

Appadurai, A. (1996). Modernity at large: Cultural dimensions of globalisation. Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalisation. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Ciafone, A. (2019). I’d Like to Buy the World a Coke”: THE “REAL THING” AND THE REVOLUTIONS OF THE 1960S in A. Ciafone (ed.). Counter-Cola a multinational history of the global corporation. Pp. 105-150. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

Mauss, M. (1973). Techniques of the body. Economy and Society, 2(1), 70-88.

Mazzarella, W. (2003). “Very Bombay”: Contending with the Global in an Indian Advertising Agency. Cultural Anthropology, 18(1), 33-71.

Mazzarella, W. (2004). Culture, Globalisation, Mediation. Annual Review of Anthropology. 33(1), 345-367.

Sassen, S. (2001). The Global City: New York, London, Tokyo. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Williamson, J. (1978). Decoding Advertisements: Ideology and Meaning in Advertising. Marion Boyers.

***

Sharayu Shejale is pursuing an integrated MA in Development Studies from Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Madras.