Besides offering a magical temporary escape from the stressful times of real life, Harry Potter’s story teaches some classic moral lessons about family, friendship, love, and unity. However, revisiting this enchanting dimension over time has made me question its gender representations. This essay probes gender biases in Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire (HP4)1. The story takes a serious tone from here, describing the return of the powerful dark wizard, Voldemort. It is where J K Rowling begins preparations for the “Final Battle for the Greater Good.”

A Window into the ‘Real’ World

Marking the start of a transition for Harry from childhood to adulthood, HP4 fits right into the category of young adult fiction, with both teenager and adult audiences. Such texts offer unique windows to societal patterns/dilemmas by focusing on crucial life choices. The audiences’ identification with characters in these texts can contribute to their understanding of and response to gender, caste, and class issues. As these novels transform into movies, their potential to emphasize hegemonic societal practices increases exponentially.

Superficial Gender Equality

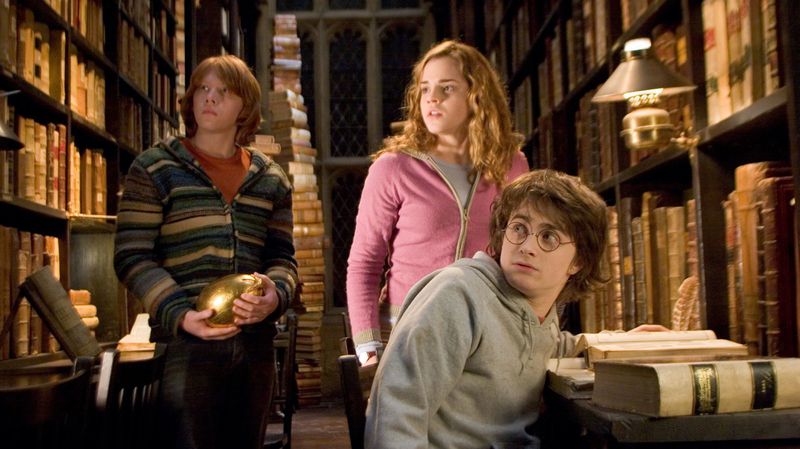

Michele Fry2 argues that Harry could not have been able to defeat Voldemort without his friend Hermione. However, Fry underlines that the lives of the female characters are in the dark until they get directly involved with Harry’s life. It seems to explain the increasing cruciality of Hermione’s role as Harry’s journey progresses. In HP4, she aids him to learn magical spells for the Triwizard Tournament, forsaking her exam revision in the process. Although confident and strong, isn’t her identity limited to being Harry’s ‘helper?’ Wouldn’t it be a better experience to watch Harry and Hermione fighting Voldemort together rather than Hermione ‘helping’ Harry fight Voldemort?

It makes me wonder whether Hermione and other female characters portray feminism as a veil to conceal gender biases. The only girl participant in the ‘prestigious’ Triwizard Tournament (Tri-“wizard” – rings a bell?), Fleur, performs the worst. Harry and Ron ‘supposedly’ save her younger sister during the second task. The Quidditch Worldcup final teams do not seem to have any female players. Hermione hates Quidditch because she hates flying (unathletic feminine stereotype?). Most characters treat her eccentric when she develops her plan of house-elf welfare.

Fry’s paper encourages me to think about ‘superficially’ strong females as a ploy to hide deep-rooted gender biases. Hermione performs exceptionally well in all subjects except the one in which Harry excels (Defense Against the Dark Arts). Characters like her and McGonagall are secondary in authority to males (Harry and headmaster Dumbledore). Why is it more challenging to imagine influential female characters equivalent to males than magical maps or transportation devices (portkeys)?

The ‘Others’

Pugh and Wallace3 discuss the absence of LGBTQ+ characters in the HP series. There are also no visible same-sex attractions in humans or magical creatures. However, some surface examples of homosexuality exist, the most popular being the “magic-phobia” of his relatives that makes Harry question the non-wizard normativity in ways similar to queers challenging heteronormativity. Another issue is suppressing characters who can challenge the hero’s solitary masculinity (the ‘Boy’ who lived).

This article helped me realize that recognizing gender constructions as a continuum rather than binaries can be vital in identifying and tackling gender biases. HP4 provides direct and indirect examples of how patriarchy oppresses women, and male-female societal patterns make other genders comparatively unworthy of respect. The oppressed suffer in their personal and professional lives, leading to their non-participation as equal peers in society.

It also makes me question whether HP4 was “queerbait” to attract more audiences. Although Rowling hinted at queerness superficially, she never seemed to represent it sexually. She announced Dumbledore as gay after the last novel’s release, but fans were disappointed at the presence of almost non-existent explicit queerness in HP movies and spinoffs. These tactics compound depression, anxiety, and social isolation. In a magical world with centaurs, sphinxes, phoenixes, merpeople, dragons, elves, and goblins, there are no genuine LGBTQ+ or independent female characters. Since HP4 represents a more mature story of hope and love than its predecessors, shouldn’t it be more inclusive regarding gender?

Complex Authoritative Patriarchy

Farah Mendlesohn’s4 paper highlights how the HP texts portray “heroism born in the blood.” While Dumbledore and Weasleys discourage the Malfoys’ emphasis on pure wizard blood, both do not fail to mention that Weasleys and Potters were among England’s oldest magical families. Dumbledore as the mighty “wizard” Voldemort ever feared, or the most influential Ministry of Magic posts occupied by “wizards” (pure/half-bloods), many of whom supposedly believe in equality of all – I found several instances of egalitarianism that hide elitism while interacting with biased gender representations. We never hear Hermione’s detailed story of overcoming her ‘muggle’ adversities in the wizarding world (possible hint towards caste discrimination?). There is also significantly less information about her family background than Ron’s, although both are Harry’s best friends.

This interplay between patriarchy and authority construction, which survives by exploiting ‘other’ genders, can at most give way to superficial equality. The HP universe seems to possess a male-dominated social structure, and the positioning of HP characters contributes to maintaining it. It also emphasizes rigid social stratification through different behaviours/rivalries between and within non-magical and magical people (primarily males). The school Sorting Hat “divides” students into houses based on their “abilities.” The Hufflepuff house rarely takes charge (lowest). HP underlines issues within patriarchy, where a few “powerful” men (elitism, classism, casteism) oppress others below them in social/professional order. I feel that it is imperative to explore these aspects to get at the core of gender representations, and this certainly is not limited to HP4. Don’t men who abuse other men have a greater chance of exploiting ‘other’ genders? Aren’t mistreated men more likely to mistreat ‘other’ genders (inferior, according to them) to vent their frustrations?

Conclusion

The issue of patriarchy seems to prevail universally in societies worldwide. Gender discrimination in young adult texts like HP4 is worth bringing to attention as they attract audiences in the growth phases of their lives. Decentering5 male authority by centring the feminine and LGBTQ+ margins can offer potential tools for social transformation. Possible questions: How might we consider gender beyond forced structures of masculinity/femininity? Is it possible for the story to rise above the illusion of ‘superiority’ and ‘inferiority’ through this process?

HP4 gender discrimination interacts with other social issues (like caste and class) in a multilayered and complicated manner. It often fails to establish that life has many grey areas rather than just being black and white. Females and LGBTQ+ never seem to trigger the story’s crucial incidents. This prejudice exists in humans and magical creatures alike. Although this essay is not an exhaustive approach to understanding the complex layers of HP4 gender representations, it indicates that Rowling’s work seems to be a story about “who” gets the privilege.

One way to explore better interpretations of such works can be by finding answers to questions like what would happen if audiences stepped away from assumptions of a gender’s supremacy? Biased gender representation has prevailed since times immemorial with no absolute solution. Reinterpreting gender constructs through famous works like HP4 can be a fundamental way to realize what it means to be human.

References:

Rowling, J. K. (2000). Harry Potter and the goblet of fire. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Fry, M. (2001). Heroes and heroines: Myth and gender roles in the Harry Potter books. New Review of Children’s Literature and Librarianship, 7(1), 157-167.

Pugh, T., & Wallace, D. L. (2006). Heteronormative heroism and queering the school story in J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series. Children’s Literature Association Quarterly (Johns Hopkins University Press), 31(3), 260-281.

Mendlesohn, F. (2001). Crowning the King: Harry Potter and the construction of authority. Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts, 12(3), 287-308.

Derrida, J. (1988). Structure, Sign and Play in the Discourse of Human Sciences. In D. Lodge (Ed) Modern Criticism and Theory: A Reader. (pp. 107-123). Longman.

***

Apeksha Srivastava is pursuing her PhD at the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Gandhinagar. This article is part of the assignment she has submitted for the course ‘Literature, Theory, and Social Context’ in Humanities and Social Sciences at IIT Gandhinagar.