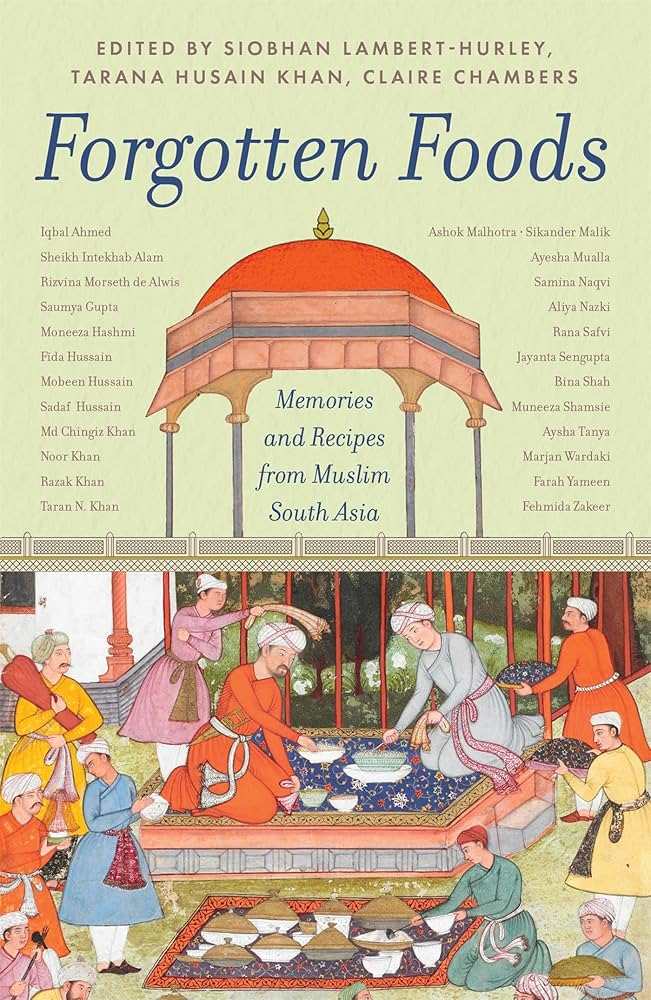

Forgotten Foods: Memories and Recipes from Muslim South Asia (edited by Siobhan Lambert-Hurley, Tarana Husain Khan, Claire Chambers and published in 2023 by Pan Macmillan) takes the reader on a scrumptious journey through historical and contemporary South Asian Muslim foodways. It is an anthology of essays, recipes, anecdotes, and reflections on Muslim food cultures in South Asia; part of the ‘Forgotten Food: Culinary Memories, Local Heritage and Lost Agricultural Varieties in India’ project funded by the Arts & Humanities Research Council in the United Kingdom. There is also a documentary, a project to resurrect heritage rice varieties in collaboration with farmers and plant scientists, and a performance piece based on Rekhti poetry.

The sociological importance of the book is reflected in the intention of the authors to emphasize the food histories of various Muslim communities as a response to the recent attacks on Muslim food cultures in India. The larger objective is to problematize the labelling of ‘Hindu’ food as quintessential ‘Indian’ food. The varied and rich collection of heritage recipes and cooking techniques in the book highlights the role of Muslim communities in shaping what is today called Indian cuisine. The collection aims at diversifying the sources of Muslim culinary traditions beyond elite households. The chapters are divided into four thematic sections and each chapter ends with a family and/or historically sourced recipe.

The first section relates food with memories of places, people, and family histories. Muneeza Shamsie’s essay invokes memories of the Partition through meticulously preserved family recipes, elaborate cooking and serving rituals, travelogues, and notes scribbled in the margins of cookbooks. Her grandmother’s travelogue of a trip to England in the 1920s uses food to make sense of newly encountered cultures. In contrast, Moneeza Hashmi remembers her father, the revolutionary poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz, through his simple tastes, almost ritualistic tea habits, and fondness for sarson ka saag (mustard greens), koftas, and parathas. Farah Yameen – in a fantastically reflexive essay – recounts her family’s traditions of celebrating Bakr Eid in Bihar. She argues that the festival remains engulfed in caste and feudal relationships of power. From the distribution of different cuts of the qurbani (sacrifice) meat to its cleaning and cooking, deep-set notions of purity and pollution are at play (p.72). Offal and other unwanted cuts of meat are not consumed by ‘upper-caste’ households, finding a place in the kitchens of cooks and domestic workers. Smell and sight, thus, become important registers to deem food disgusting and undesirable. Notions of purity and gendered labour feature in Taran Khan’s essay on ‘outside food’. She recalls childhood picnics in the 1990s that meant carrying along a part of the home kitchen as “eating out carried a sense of living dangerously” (p.50). Planning, cooking, and carrying these picnic meals invariably fell to the women of the family. Rizvina Morseth de Alwis writes on the unique place of Sri Lankan Malay cuisine in the complex history of Malay Muslim migration to Sri Lanka. She aptly describes the tension between preservation and assimilation faced by migrant communities. Many Sri Lankan Malay dishes like the Malay achar have found a place in the country’s cuisine, while others like babath-puruth (a tripe curry) have remained marginalised due to their “offensive” nature.

The second section emphasises food’s role in shaping social identities. Jayanta Sengupta writes about the Calcutta Biryani, tracing how its development signified the adoption of Indo-Persian cuisine in Bengal. The history of food encounters between Bengal and Persianate cultures depicts the hybrid nature of what we consider traditional food; thereby problematising claims of ‘authentic’ cuisines uninfluenced by other cultures. Yarkandi pollo (pulao) lies at the centre of Fida Hussain’s essay on the culinary heritage of Ladakhi Muslims. Ladakh’s food heritage is a testament to the region’s unique topography, ecology, and its location at the crossroads of the Silk Route. The Ladakhi tradition of baking is an influence of Kashmiri and Central Asian traders, with Bazari Tagi (bread from the bazaar) being popular during Ramzan. Saumya Gupta’s essay takes us to the world of Urdu cookbooks in the mid-20th century. Emerging with the popularisation of print culture, these cookbooks were written by and for middle-class women of Awadh. The methodical listing of names and places makes these cookbooks representative of ‘Ashraf’ domesticity among middle-class women of that time (p.101). Gupta argues that the community of readers and contributors created by these cookbooks transcended restrictions placed by small towns, national borders, tradition-modernity binaries, and religion. Siobhan Lambert-Hurley’s brilliant piece—written in the backdrop of Junaid Khan’s lynching in 2017—draws attention to the horrific consequences of homogenising and stigmatising Indian Muslims as ‘beef eaters’. She centres different Muslim histories (sourced from travel writings of South Asian Muslim women over three centuries) to illustrate “how symbolic meanings attached to food can vary within a nation, community or cultural grouping over time” (p.107). These travelogues (written in the colonial period and its immediate aftermath) reveal that contrary to popular belief, food was not commonly used to differentiate Hindus from Muslims; rather it was a marker of distinction between Indian Muslims and other groups of Muslims and non-Muslims in places like London, Ohio, and even Mecca. The distinction was made in all the five stages of production, distribution, preparation, consumption, and disposal described by Goody (1982). The essay ends with a recipe of Junaid’s favourite ‘Soyabean Biryani’; brimming with irony and reminding us that binaries, after all, reflect the continuities and ruptures of history.

The third part is concerned with the myriad intersections of the traditional and the modern. Aliya Nazki shares her ‘authentic’ Rogan Josh recipe; warning us to keep our tomatoes and garam masalas hidden when cooking Kashmiri food. While what counts as authentic is forever evolving — for a people grappling with attacks on every other aspect of their identity, preserving the authenticity of food becomes a means of survival. Authentic food, then, becomes an important identity marker to register one’s presence in history. This is the reason why Kashmiris (much like Palestinians) find it crucial to preserve the authenticity of their cuisine over generations (pp.162,164). Sheikh Intekhab Alam’s essay revolves around the theme of migration and how the tradition of distributing food to relatives on certain special occasions serves as a means of reviving relationships among Odia Muslims. This ‘love tradition’ called ‘Bakhra’ is attributed to various Islamic teachings encouraging the distribution of food to one’s relatives (p.168). The Bakhra tradition is not immune to the ‘gastro-politics’ (Appadurai, 1981) surrounding the social transactions of food. For instance, the son-in-law’s family usually receives a more lavish spread of food (p.169). Alam’s account of the inability to cook strong-smelling food like dried fish after migrating to Delhi reminds us how food cultures of marginalised communities are profiled through visual and olfactory aesthetics into ‘dirty food’, thus reproducing the hegemonic caste logic (Kikon, 2022). Migration and ‘home-making’ practices through food are also the focus of Razak Khan’s essay on the Afghan community in Berlin. He uses the concept of hambastagi (solidarity) to study migrant food as an affective archive of displacement, survival, and healing (p.193). The essay ends with a recipe of Qabuli Pulao cooked through French techniques reflecting the ever-evolving, composite nature of migrant cuisine.

The final section of the book explores the history and diversity of regional cuisines. Sadaf Hussain’s tempting essay celebrates the glories of the Bihari Kabab characterised by its thinly sliced pieces of meat (called the parcha cut) and unique texture. Rana Safvi’s essay is testimony to the omnipresence of Dal, from being a favourite of the 16th-century Safavid emperor to being the inspiration behind the construction of Delhi’s Moth ki Masjid. A variety of dals have been discovered at excavation sites of the Indus Valley Civilisation, andhave been mentioned in Sanskrit, Persian, and Urdu literature since antiquity. Not limited to gustatory matters, urad dal was also used in lime mortar for construction purposes. Often considered the poor man’s meal, yellow mung dal fritters marked the beginning of coronation festivities during the reign of the last Mughal Emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar. Today, celebrations in Rajasthan and parts of Uttarakhand begin with the frying of dal vadas. The frying of dal vadas also marks the end of the mourning period of Muharram in west Uttar Pradesh (pp. 259-261). Aysha Tanya traces the rich history of Mappila (Malabar Muslim community) cuisine — influenced by Arabic, English, Dutch, Portuguese, and French culinary traditions — through the versatile egg, an indispensable part of Mappila kitchens. Mappila food is reflective of the region’s rich trading history, reminding us how the movement of food points to a history of globalisation way older than the formation of modern nation-states (Gupta, 2012).

This anthology is immensely helpful in understanding the semiotic nature of food placed in its social context. Allowing us a glimpse into historical and contemporary kitchens, it broadens and complicates our understanding of both ‘Indian’ and ‘Muslim’ food. The essays in this collection explore themes of memory, identity, migration, and heritage; through a mix of academic research, family anecdotes, and heirloom recipes. The book encapsulates the intimate role of food in structuring the social — one delectable recipe at a time — which makes it a valuable resource for scholars and food enthusiasts alike. A word of caution: do not read on an empty stomach! The writing may invoke intense hunger pangs and an irresistible urge to try out all the recipes.

References

Appadurai, A. (1981). Gastro‐politics in Hindu South Asia. American Ethnologist. 8(3): 494-511.

Goody, J. (1982). Cooking, Cuisine and Class: A Study in Comparative Sociology. Cambridge University Press.

Gupta, A. (2012). A Different History of the Present. In K. Ray and T. Srinivas (eds.) Curried Cultures: Globalization, Food and South Asia (pp.29-46). University of California Press.

Kikon, D. (2022). Dirty Food: Racism and Casteism in India. In J. F. Cháirez-Garz, M. D. Gergan, M. Ranganathan and P. Vasudevan (eds.) Rethinking Difference in India Through Racialization: Caste, Tribe, and Hindu Nationalism in Transnational Perspective (pp. 86-105). Routledge.

***

Neha Sharma is a PhD research scholar at the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences (HSS), Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Guwahati.